landlubbers on the water

The Council of State recently ruled that all houseboats in the Netherlands are a structure. This has quite a few implications, Jasper de Haan makes a plea to use the spatial legislation on water that has now become necessary to experiment with a new kind of regulation. A regulation that encourages and rewards rather than prescribes and prohibits. And perhaps those water regulations could then later be used on land.

movable or immovable

Houseboats are strange things. By their very nature they float, at least when they are good, and are therefore movable property. But most houseboats are securely tethered to the shore, connected to all utilities and nowadays almost all to the sewer system, and therefore virtually immoveable. So apart from some gentle rocking, immovable. The judge and, with him, the Council of State now think so too. The bottom line is that a houseboat must now be considered a structure. And that has quite a few consequences. Because a building has to comply with, among other things: the Environmental Law (General Provisions) Act (WABO), the Housing Act, the Building Decree, the Construction Ordinance and the Welstands Memorandum. Ready are you, because the consequences are hardly incalculable. Not one houseboat in this country currently complies with the building code. Mooring permits and the like are not environmental permits and are often issued by entirely different officials. And we have quite a few houseboats, 2,800 in Amsterdam alone and 12,000 nationwide. And there are more every year. The potential of waterfront living is increasingly recognised and encouraged. Wonderful, but the regulations for it still lag behind. What to do

What does not help is that the term structure is not defined in the Housing Act or the Wabo. For a definition of a structure, the Wabo refers to the VNG's model building regulation.

"any structure of any size made of wood, stone, metal or other material, which at its place of destination is either directly or indirectly connected to the ground, or directly or indirectly supported in or on the ground, intended to function locally."

And to further complicate matters, according to the Ministry's mandated definition document (the SVBP 2012), the zoning world defines a structure as follows:

"A building structure of any size that is directly and durably connected to the earth."

And what is that "directly and durably connected to the earth"?

The court finds that a piece of string used to tie up the boat is sufficient, as long as the thing is intended to function on site. And although, curiously, we thus have no unambiguous definition of the term structure, the highest court has now spoken. A houseboat is a structure and must therefore, among other things, comply with the building code. And that's not so easy.

What goes wrong?

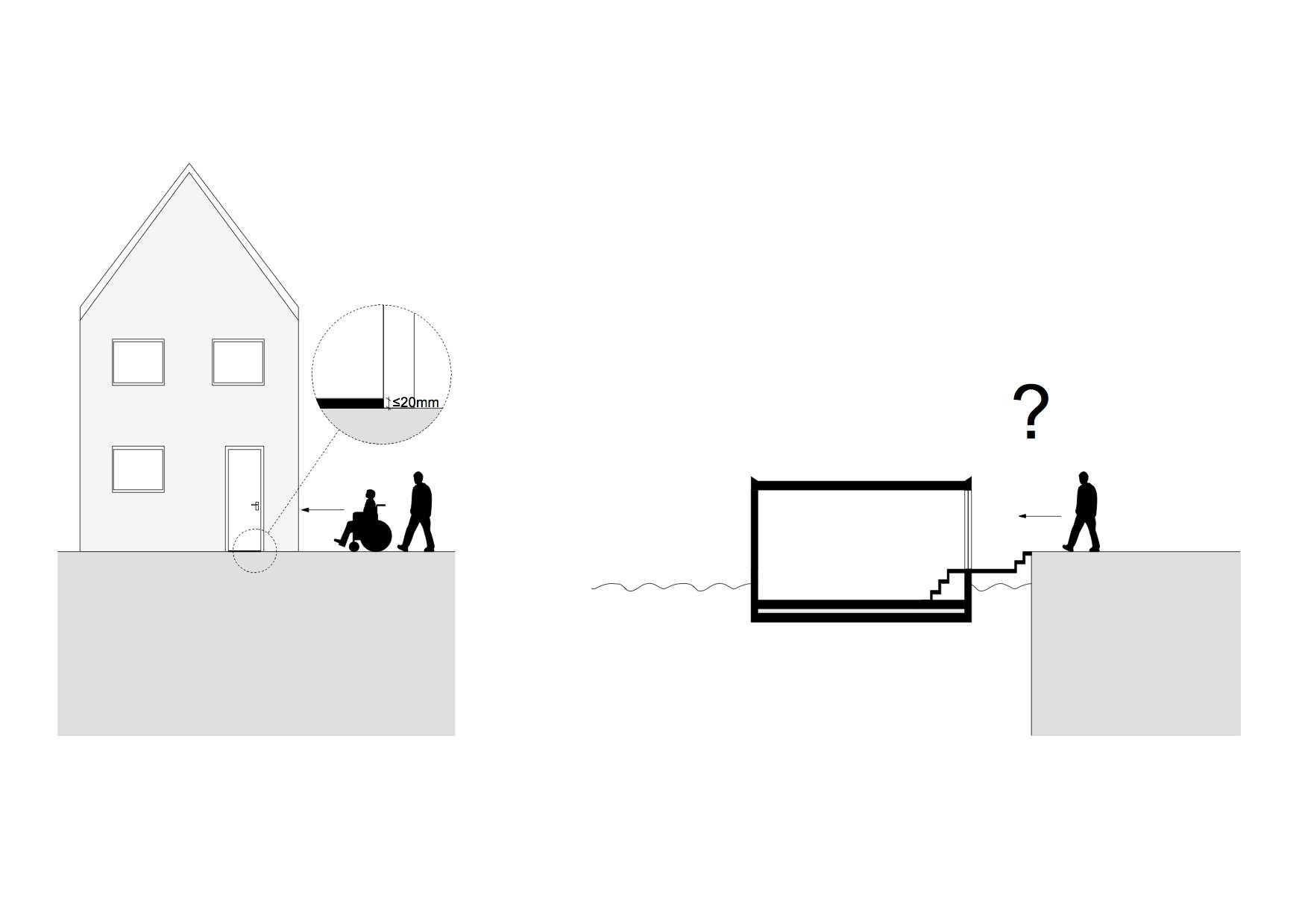

- To start with the front door, the height difference from the connection to the adjoining ground floor must not exceed 20 mm, according to the building code. Just try to get that done from a quay wall that is one-and-a-half metres above the water line and a ground floor of a houseboat that is one-and-a-half metres below the water line.

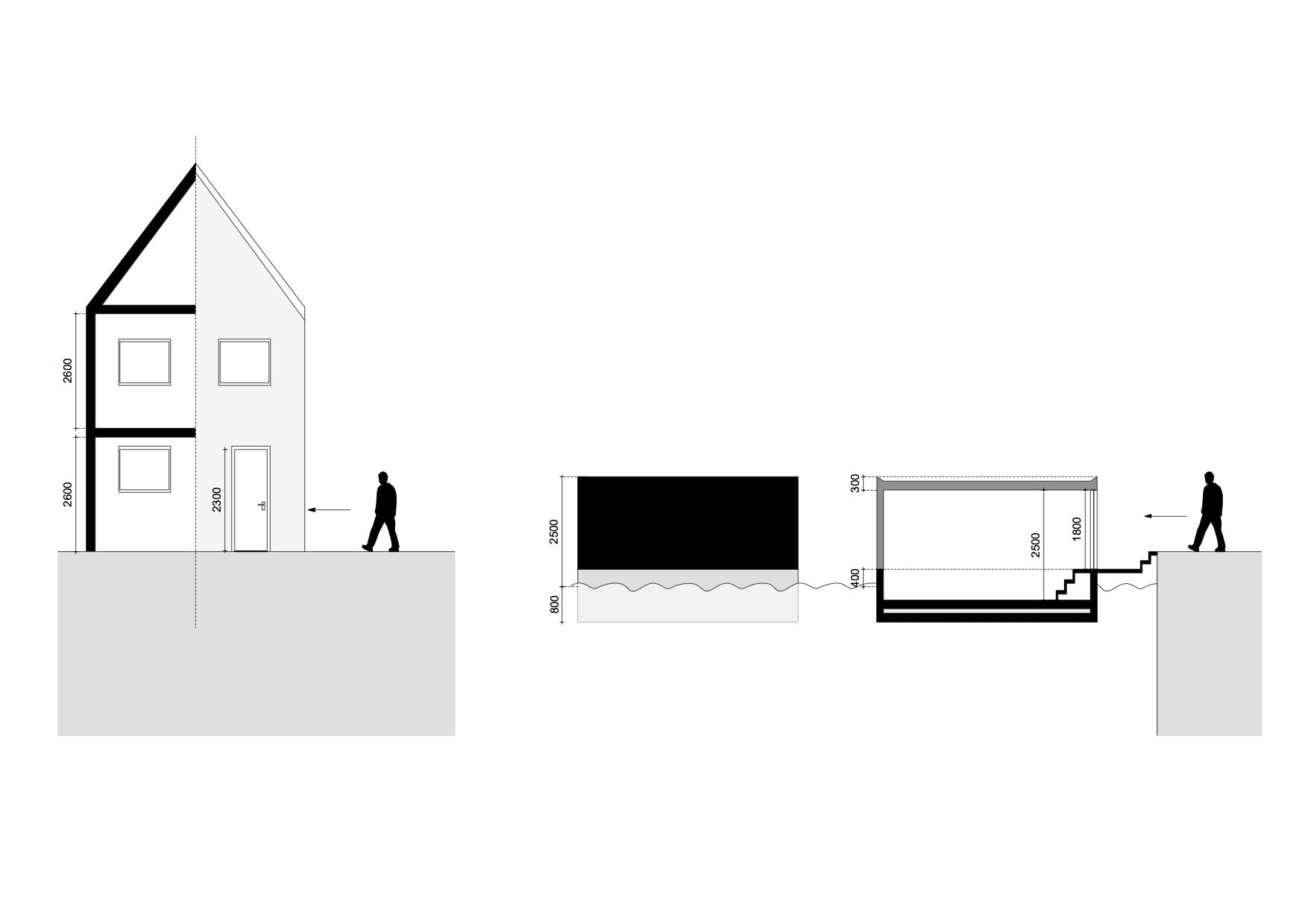

- Or what about provisions concerning headroom and clearance height? The Building Decree stipulates a headroom of 2.6 metres and a clearance height of 2.3 metres. The maximum height of a houseboat is generally set by municipalities at 2.0 to 3.0 metres above the waterline. This is understandable, as it allows for some view of the water from the shore. With a freeboard (the height above the waterline of the watertight part of the structure) of 0.3 to 0.4 metres, which is necessary in connection with flooding, waves and insurance, a maximum construction height of 2.5 metres leaves only 2.1 metres for a door. And then you still have to deduct the door frame, threshold and roof. So it's not possible.The same problem arises with the normal headroom (2.6 m) that a living space must have. Again, assuming a maximum height above the waterline of 2.5 metres, a roof edge of 100 mm, roof insulation of 100 mm and a sloping roof construction quickly add up to 300 mm. That quickly takes up the first 0.5 metres. If we add the required headroom of 2.60 metres to that, the top of the ground floor is 0.6 metres below water level. If we then add a normal insulated VBI concrete floor with a sand-cement screed of about 350 mm and a 'crawl space' for ventilation, hull inspection and piping of 0.5 metres, and of course the floor of the concrete tank itself, which is 150 mm thick, we are already 1.60 metres below water level. And it is not that deep along the waterfront in the Netherlands. Another disadvantage of this is that the parapet of the windows would then be at a height of 1 metre. Looking outside from your armchair would then no longer be possible.

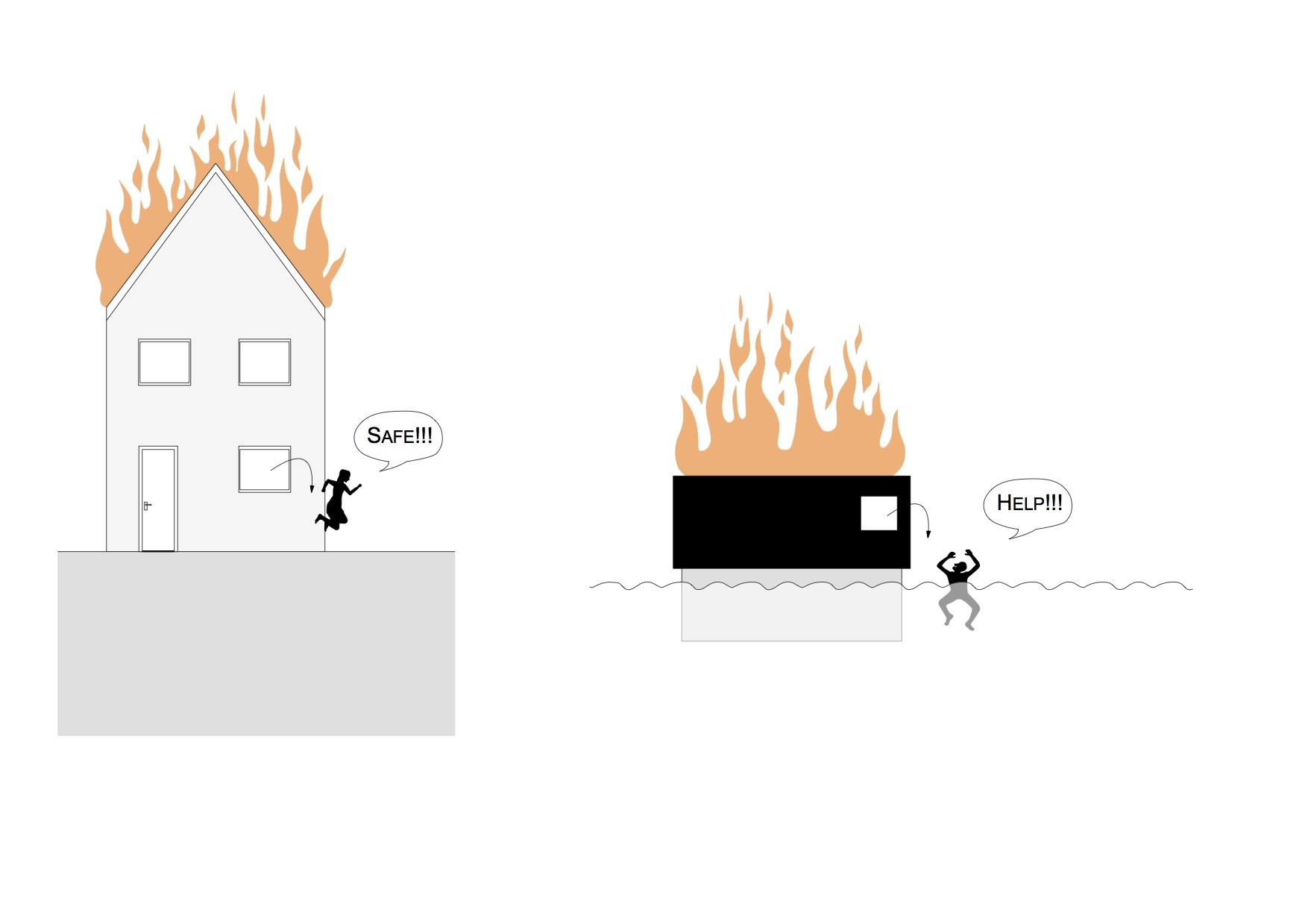

- In the Building Decree, escape routes, for example in the event of a fire, lead to what is known as the adjacent area. Now, the adjacent area of boats is generally water or a jetty/quay/shore. And although a nice dive out of the window into the water in the event of a fire on a boat may seem like a better escape route than jumping out of the window of a house into the front garden, it is not considered equivalent by the regulators.

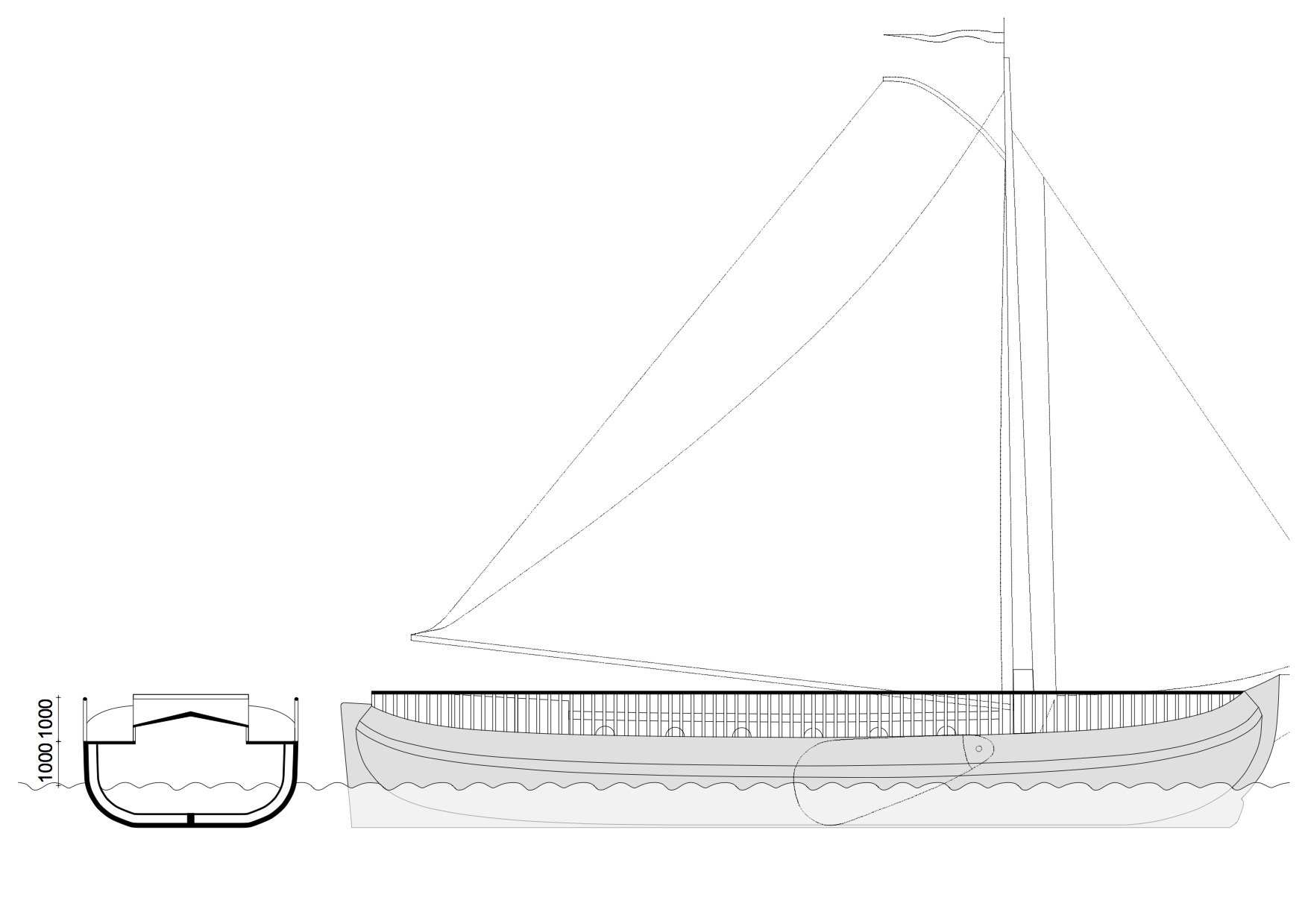

- Or what about an impassable fall protection barrier of the correct height on a Tjalk, to prevent you from falling into the water from a height of one metre? It is impossible to make an original ship, some of which are 100 years old, comply with building regulations. Probably no one really wants that, and unfortunately, bumping your head is just part of life on these vessels. And what are you supposed to do if you live in a beautiful, virtually original Klipper or Tjalk? You could sail away in it, but the highest court has now ruled that you have a structure and no longer a ship. Simply because your ship is securely moored and connected to utilities and functions on site.

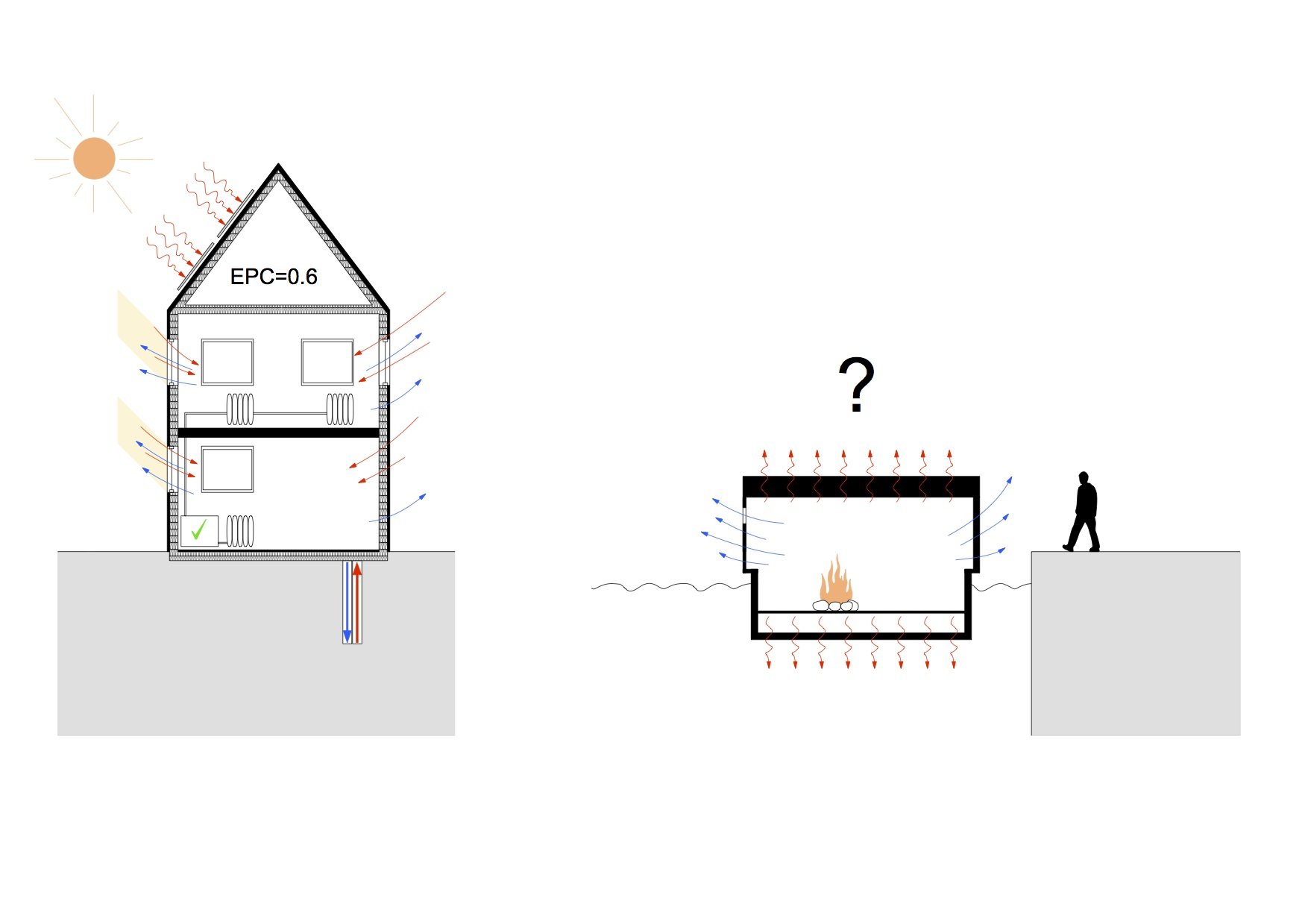

This is not to say that there should be no regulations governing waterways. In fact, there are areas where the lack of regulations for houseboats compared to houses on land creates glaring legal inequalities. For example, an EPC that is currently 0.6 and will slowly tend towards 0.0 by 2015 for houses on land is now fully accepted, but you can still build a new houseboat without any insulation or double glazing, which you then cheerfully heat throughout the winter with painted wood, diesel or, even cheaper, salad oil from Aldi to keep it warm. As a result, entire canals and harbours are sometimes shrouded in thick 19th-century smoke for months on end during the winter. We can be romantic about it, but it is actually strange that we accept this in the 21st century.

Whereas the owner of a canal house in Amsterdam located in a UNESCO World Heritage Site is not permitted to make any significant changes to their property, the owner of the houseboat moored three metres away in the canal is permitted to make virtually any changes they desire.

In short, something needs to be done, and quickly. We have had a kind of parallel building regulation for caravans for some time now. Every article or table has a separate section for caravans. But whether it is such a good idea to develop another 'parallel' building regulation for houseboats, ships and floating houses is questionable.

It is undoubtedly the fastest and cheapest way to create some emergency legislation and resolve the worst gaps and problems. But wouldn't it be much more interesting to use the legislation that is going to be introduced for houseboats to test what the much-desired flexible regulations could look like? How can we create regulations that allow maximum freedom, but also guarantee safety, usability and beauty? Regulations that do not prescribe and punish, but reward and encourage. Especially in zoning plans. And then preferably go all the way and integrate the zoning plan with the aesthetic guidelines into a single document. Regulations where maximum freedom goes hand in hand with maximum spatial quality. Such an experiment might be more interesting than trying to make the existing land regulations as waterproof as possible.

This article was also published on Archined.nl and is based on an extensive study of regulations on water and spatial quality, which was made possible thanks to a contribution from the Stimuleringsfonds voor Architectuur (Architecture Incentive Fund), now known as the Stimuleringsfonds voor de Creatieve Industrie (Creative Industries Incentive Fund). All drawings are part of the report of that study.

Jasper de Haan is an architect and houseboat advisor for the Amsterdam Committee for Aesthetics and Monuments. He writes this article in a personal capacity.

For the full research report "Landlubbers on the water," click here (1.79 MB).For the full research report "Landlubbers on the water," click here (1.79 MB).