20 July 2011

It was announced today that the grant application we had submitted to the Incentive Fund for Architecture to do research into more combined regulations for construction with water living as a case study has been awarded. That means we can now really get started on this research in which we are collaborating with Martine van Lier of the Erfgoedwerf. We are very much looking forward to this. Below is a brief summary of the issues.

floating houses

regulations

Houseboats, houseboats, arks, barges or whatever you want to call them, in any case floating shelters on water, have been part of the landscape and the city for centuries. Movable in principle but practically often, apart from some rocking, as immovable as a house. In a sense, these objects are perhaps an even more important part of the public space than, say, the surrounding closed façade walls of a canal in which they are located, if only because they are all-sidedly approachable in the open space and because, in addition to the four façades, the fifth façade is actually perceptible from the street or bridge. They therefore often, in places where there is water, largely determine the spatial quality of the public space. But they almost completely evade the regulations to which the immovable part of the space is subject. Especially in places with special spatial qualities (World Heritage Sites, protected cityscapes, high landscape values, etc.), this leads to curious legal inequalities and differences in quality. But it also has very attractive aspects, as for once

all kinds of (superfluous) rules do not apply. It is striking that the attitude of many municipalities towards living on the water is ambivalent, to say the least. On the one hand, the diversity on the water and the preservation of historical vessels is appreciated, while on the other hand, the policy can be called restrictive or even repressive. This leads to a slow but steady decline in the number of moorings, while the focus on living on the water is actually increasing. It is clear that many municipalities do not know how to formulate policy on what they would find undesirable but, more importantly, desirable developments regarding living on water. The Netherlands currently has over 10,000 houseboats, 3,000 historical vessels and 550 charter vessels.

Regulations and architectural quality:

Floating houses are not subject to the Housing Act, the Building Decree does not apply and they are usually not included in zoning plans. Therefore, no building permit is granted for a new houseboat, but a mooring permit. This is also not granted by the VROM or RO department of a municipality, province or state, but usually by a department that deals with the management of the (waterways). Curiously, a few municipalities do apply standpoint criteria and the standpoint committee considers applications for conversion or replacement permits. One would therefore expect that the arsenal of houseboats in this country would be of stunning, innovative and spectacular architectural quality. After all, no regulations that could hamper apply, only architectural quality-enhancing aesthetic criteria and commissions should be able to push the design to great heights.

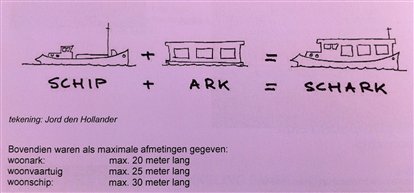

Nothing could be further from the truth, unfortunately. The average houseboat in this country does not surpass the quality of the worst examples of catalogue houses, and the urban planning or landscape incorporation can generally not be described as anything other than extraordinarily boorish. Even the interventions on houseboats and 'scharken' often show little care or craftsmanship. Besides

all other causes of wretched architectural and urban planning quality in general, two important additional problems apply to floating homes. These are the quality of the only applicable regulations for houseboats (the building standards memorandum) and the fact that the market for building and designing houseboats with a concrete hull has become an oligopoly.