A handful of diamonds in a sea of junk

The IABR 2016 is about the Next Economy. We don't yet know what that Next Economy will be. What we do know is that it will be different, different from what it is now. Architects and urban planners always design things that don't yet exist and that they don't yet know exactly how they will turn out. They project what has not yet been built into the future.

Designers are experts in dealing with uncertainties and ambiguities.

However, in order to deal with these uncertainties, they often create frameworks or structures whose exact details only become clear decades later. The question is, of course, where these frameworks are conceived or developed. In this Biennale, four design studios have been set up to investigate the possible directions that such a Next Economy could take. The IABR's Project Atelier Groningen is investigating the spatial consequences of the energy transition from fossil fuels to sustainable energy for the city and province of Groningen. It is interesting to first look at the previous energy transition from wood to coal and oil in the twentieth century and to learn from what actually happened in that century.

In the conclusion to his book on the twentieth century, The Future of Architecture since 1889, architectural historian Jean Louis Cohen writes that the twentieth century was merely a brief interlude in the world's ongoing drama. And that what can be called architecture will be nothing more than a handful of diamonds in a world full of rubbish. The twentieth century is over and it seems that we are returning to normal, according to Cohen. The normal in which the term Edifice Complex, coined by Deyan Sudjic, can happily continue to proliferate. The complex whereby a single ruler builds cities with money and architecture while the rest of humanity lives, works and recreates in rubbish. That twentieth century that we find so normal, if only because the vast majority of us were born in it, turns out to be an anomaly. The twentieth century in which it seemed for a moment that good architecture and urban planning were available to everyone. In which we in the West built sewers, water pipes and bathrooms in well-ventilated houses, which, in combination with much better healthcare, made all kinds of misery disappear. The twentieth century in which we also had world wars and a holocaust. But also the first man on the moon and in which the world population grew from 1.5 billion to 6 billion people. What made the twentieth century so special?

Oil

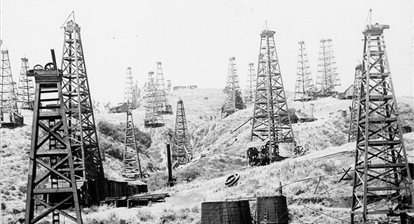

According to Carola Hein, professor of architectural history at TU Delft, that is oil, or rather fossil fuels. If that is the case, we should perhaps let the twentieth century begin in 1870 – the year in which John D. Rockefeller founded his first oil company (Standard Oil) – and end with the oil crises of the 1970s. In her inaugural lecture at TU Delft in January of this year, Hein convincingly demonstrates how oil has influenced, if not determined, urban planning and architecture, not to mention society as a whole, including the arts.

Without oil, there would be no plastic, no petrol, no cars and therefore no motorways. For example, the driving force behind Plan Voisin, in which the old city centre of Paris was demolished to make way for Le Corbusier's Ville Radieuse, was the car manufacturer Voisin. Another example can be seen in the documentary Bikes versus Cars, which shows how the car lobby, i.e. General Motors bought up the beautiful and well-functioning public transport system of Los Angeles and then simply abolished it in favour of more cars. An extensive network of cycle paths was also demolished in order to make L.A. the car city of the US. The port of Rotterdam is unthinkable without oil. The arrival of the oil industry has had an impact on The Hague, where the headquarters of those oil companies were established, far away from the storage tanks and refineries. Hein calls this Petrolscapes: landscapes created by the oil industry and everything associated with it. Almost invisibly, the oil industry has influenced us and made us who we are.

Or what about all the efforts made by petrol and tyre manufacturers to encourage car owners to drive more and more, from free road maps and travel guides to the still authoritative restaurant reviews in the Michelin Guide? This is even more evident in architecture that seems to be directly based on the structures required for the oil industry, such as refineries, drilling platforms and fertiliser factories. Examples include Constant Nieuwenhuis' New Babylon and Peter Cook's Plug in City, or built examples such as the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the library in Rotterdam and the Klinikum in Aachen. Without oil and oil companies, there would be no petrol, no cars, no conveyor belts, no car tyres, no motorways, no suburbs and no Chartre d'Athenes.

The Athens Charter was drawn up during the 4th CIAM Congress in Athens in 1933, chaired by Van Eesteren. It was then published ten years later, in an edited form by Le Corbusier, in occupied Paris. Among other things, it advocates a separation of living, working, traffic and recreation. There is something to be said for this, because let's be honest, who wants to live next to an oil refinery or have a blast furnace in their backyard? Nor does it seem sensible to locate a fireworks warehouse in the middle of a residential area, or to have a Boeing flying over your chimney every ten minutes. So there was something to it. But looking back now, eighty years later, a lot has been lost with that brutal separation of living, working, recreation and traffic. We now have monotonous industrial estates and office parks where you could fire a cannon after seven o'clock without hitting anyone. Monotonous residential areas where all the cars queue up every morning and evening. And city centres with fewer and fewer shops. Because we buy things online or in a large shopping centre next to the motorway. In those same city centres, there are now lots of coffee shops, bars, hotels, restaurants and museums. 'The city centre as Disneyland', as Michael Sorkin wrote in his book Variations on a Theme Park in 1992. Hardly anyone lives or works in the historic city centres of Venice or Amsterdam, for example. Another exampleThe Athens Charter was drawn up during the 4th CIAM Congress in Athens in 1933, chaired by Van Eesteren. It was then published ten years later, in an edited form by Le Corbusier, in occupied Paris. Among other things, it advocates a separation of living, working, traffic and recreation. There is something to be said for this, because let's be honest, who wants to live next to an oil refinery or have a blast furnace in their backyard? Nor does it seem sensible to locate a fireworks warehouse in the middle of a residential area, or to have a Boeing flying over your chimney every ten minutes. So there was something to it. But looking back now, eighty years later, a lot has been lost with that brutal separation of living, working, recreation and traffic. We now have monotonous industrial estates and office parks where you could fire a cannon after seven o'clock without hitting anyone. Monotonous residential areas where all the cars queue up every morning and evening. And city centres with fewer and fewer shops. Because we buy things online or in a large shopping centre next to the motorway. In those same city centres, there are now lots of coffee shops, bars, hotels, restaurants and museums. 'The city centre as Disneyland', as Michael Sorkin wrote in his book Variations on a Theme Park in 1992. Hardly anyone lives or works in the historic city centres of Venice or Amsterdam, for example. Another example

But perhaps there is a solution to all this. According to cycling activists in Sao Paolo, traffic jams are their friend. The more traffic jams there are, the greater the urgency that things cannot continue as they are and that something must be done. Another ally in the fight for change is the finite nature of fossil fuels. Even if they are not actually running out, global warming makes further CO2 emissions unacceptable. Something must be done.

It is also in the newspapers every day and is repeated ad nauseam in books and pamphlets, in countless policy visions and visions of the future by all kinds of governments, formulated in increasingly abstract terms: everything is going to change. It has to be more sustainable: self-driving cars are coming, we are going to fill the North Sea with wind turbines and put solar panels on all roofs. The Next Economy will necessarily be circular. We will turn smog into diamonds. Smart Grids will replace the current networks. The Internet of Things will rule us. When the wind blows nicely and the sun shines on weekends, Germany produces so much subsidised sustainable electricity that energy prices become negative. It's not just going to change, it's already changing. And those changes are going to change the city. Forever. At least, that's the claim. In his book Smart Cities, Maarten Hajer talks about a transition. But some people don't shy away from the term paradigm shift. But is that really the case? And what can our profession, our ancient, 5,000-year-old profession, actually contribute to that?

In 2006, architect Willem Jan Neutelings gave a lecture at The Projective Landscape conference in Delft. In it, he said that he had also read and heard that architecture and urban planning would change forever with the advent of the internet, among other things. This new technology would shake the foundations of ideas about architectural space. He had indeed noticed this in hotel rooms. Hotel rooms are straightforward: a bed, a chair and a table. Since people are on average about 1.6 to 2 metres tall, beds are usually 2 metres long and 0.75 metres wide. In addition to a place for that table and chair in such a hotel room, Neutelings had noticed an important architectural innovation a few years ago. A small hole in the wall measuring 1 x 1 cm: the data socket. These sockets had since disappeared again due to the rise of Wi-Fi. And apart from that, a hotel room basically looked exactly the same as it did a thousand years ago. In short: will the phasing out of fossil fuels and the transition to sustainable energy really change architecture and urban planning? Does the advent of the self-driving car, the smart grid, 3D printing, robots and the smart city as a whole really have the same impact as the advent of the car or the transformation of early nineteenth-century society into that of the late twentieth century? We still sleep in beds, eat at tables and sit on chairs. And what if Co

In his essay in Oase #92, ‘Traditional, subtly innovative and inevitably modern’, Vittorio Magnago Lampugnano shows that the glorification of the new or the latest in virtually all art forms, but especially in architecture and urban planning, is an eighteenth-century invention. Whereas categories such as harmony, completeness, balance and perfection had previously been important in forming an opinion about a work of art, suddenly it was dissonance, incompleteness, surprise and, above all, innovation that mattered. No longer was the craft of the designer, who steadily builds on the proven knowledge and skills of his predecessors, central, but rather the degree of innovation and the perceived cross-disciplinary quality of the work. If we consider the twentieth century to be the century of modernism and if we consider that modernism to be a cocktail of three revolutions – the French, the industrial and the Russian, representing the Enlightenment and science, the belief in technology and progress, and a socio-economic component, respectively – then, apart from that social component, we are perhaps still far from postmodern and still very much modern. But what we generally call modern or modernist is actually no longer new. It is part of the much larger history to which we must relate, whether we like it or not. So if the twentieth century was an anomaly and if the compelling forces of the oil-dollar-fuelled entities.

In his essay in Oase #92, ‘Traditional, subtly innovative and inevitably modern’, Vittorio Magnago Lampugnano shows that the glorification of the new or the latest in virtually all art forms, but especially in architecture and urban planning, is an eighteenth-century invention. Whereas categories such as harmony, completeness, balance and perfection had previously been important in forming an opinion about a work of art, suddenly it was dissonance, incompleteness, surprise and, above all, innovation that mattered. No longer was the craft of the designer, who steadily builds on the proven knowledge and skills of his predecessors, central, but rather the degree of innovation and the perceived cross-disciplinary quality of the work. If we consider the twentieth century to be the century of modernism and if we consider that modernism to be a cocktail of three revolutions – the French, the industrial and the Russian, representing the Enlightenment and science, the belief in technology and progress, and a socio-economic component, respectively – then, apart from that social component, we are perhaps still far from postmodern and still very much modern. But what we generally call modern or modernist is actually no longer new. It is part of the much larger history to which we must relate, whether we like it or not. So if the twentieth century was an anomaly and if the compelling forces of the oil-dollar-fuelled entities.

And that is exactly what the Groningen project workshop is trying to do.

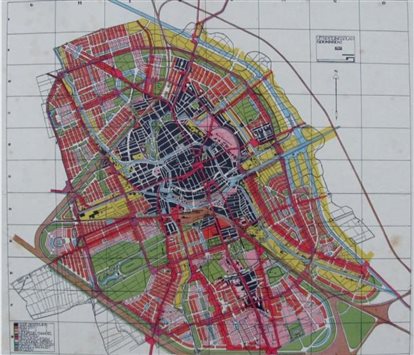

The studio attempts to answer the question of what the actual spatial impact and opportunities are of the transition from fossil fuels to sustainable and, above all, smart energy. These opportunities lie primarily in the fact that self-driving electric cars mean fewer cars are needed. Because these cars are cleaner, there is much less noise and air pollution. This literally creates more space in the city. The buffer zones against noise and exhaust fumes around motorways are no longer needed, or are needed much less. Far fewer parking spaces are needed, as are petrol stations and garages. We can also manage with less wide roads. We can say goodbye to Carola Hein's Petrolscapes. The question is how we can use these residual spaces to enrich the urban space as a whole. And how to link the technical infrastructure, the pipes, to the physical space. In their plans, they draw on older, proven models. Their starting point is the plan that Berlage drew up together with the Groningen city architect Schut in 1931.

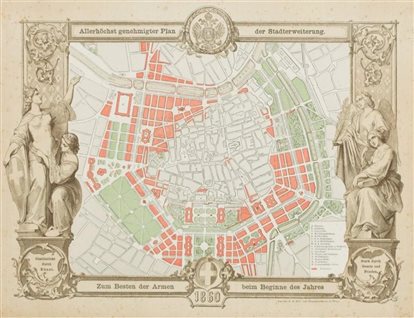

Remnants of the ring road that characterised this plan are still visible in the urban fabric of Groningen. With the connection of the Ring to the N46, the western part of that ring road is no longer regional but local. In doing so, they are looking to the most famous ring road in the world, the Vienna Ringstraße. Built in 1857 on the orders of Emperor Franz Joseph as the showpiece of the Habsburg Empire. Sigmund Freud is said to have walked around it every day. But early modernist architects such as Loos and Wagner did not like it at all. Far too many ornaments and ostentatious palaces of the Nouveau Riche. But at that time, someone else was also walking around the Ringstraße, and that was Camillo Sitte, who published his book Der Städtebau nach seinen künstlerischen Grundsätzen (Urban Planning According to Its Artistic Principles) in Vienna in 1889. And that is the book to which virtually all of Berlage's urban planning works, such as Plan Zuid in Amsterdam and, of course, the Groningen expansion plan, owe a debt of gratitude. In his book, Sitte explains how to create high-quality, pleasant urban spaces. He was critical of the Ringstraße, and perhaps the very spacious design of that ring road in Vienna was the reason for his book, given the plans for improvements he included in Städtebau. But the combination of closed building blocks that together create urban, secure spatial space, with lots of greenery, is the basic material for the city in his artistic g

Greenery in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was much more part of the continuous public space than in the twentieth century. Whereas in modernist urbanism, greenery is the field for the object on it - such as Villa Savoye or the apartment buildings from the Ville Radieuse - in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century city, greenery is part of the transit space or the street. Be it the Heemraadsingel in Rotterdam or the Lange Voorhout in The Hague. In Groningen, too, the newly planned ring road is part of the green structure.

It is nice that a city that has perhaps the most Sitte-like succession of squares and plazas in the Netherlands - I mean the sequence from East to West right through Groningen, from A-kerhof and the Vismarkt via the Grote Markt (11) to the Martinikerkhof - for its leap into the twenty-first century is now once again leaning on the ideas of Berlage and Sitte.

Jasper de Haan March 2016

This text previously appeared in: Thoughts for a smart energy city,Groningen - Nordic City, March 2016, Municipality of Groningen, Groningen.It is the result of a study by the Atelier Stadbouwmeester Groningen.

Wouter Bolhuis, Jeroen de Willigen, Jan Martijn Eekhof, Erik Dorsman, Jasper de Haan