Landlubbers on the water

The Council of State recently ruled that all houseboats in the Netherlands are a structure. This has quite a few implications, Jasper de Haan makes a plea to use the spatial legislation on water that has now become necessary to experiment with a new kind of regulation. A regulation that encourages and rewards rather than prescribes and prohibits. And perhaps those water regulations could then later be used on land.

movable or immovable

Houseboats are strange things. By their very nature they float, at least when they are good, and are therefore movable property. But most houseboats are securely tethered to the shore, connected to all utilities and nowadays almost all to the sewer system, and therefore virtually immoveable. So apart from some gentle rocking, immovable. The judge and, with him, the Council of State now think so too. The bottom line is that a houseboat must now be considered a structure. And that has quite a few consequences. Because a structure has to comply with, among other things: the Environmental Law (General Provisions) Act (WABO), the Housing Act, the Building Decree, the Construction Ordinance and the Welstands Memorandum. Ready are you, because the consequences are hardly incalculable. Not one houseboat in this country currently complies with the building code. Mooring permits and the like are not environmental permits and are often issued by entirely different officials. And we have quite a few houseboats, 2,800 in Amsterdam alone and 12,000 nationwide. And there are more every year. The potential of waterfront living is increasingly recognised and encouraged. Wonderful, but the regulations for it still lag behind. What to do?

What does not help is that the term structure is not defined in the Housing Act or the Wabo. For a definition of a structure, the Wabo refers to the VNG's model building regulation.

"any structure of any size made of wood, stone, metal or other material, which at its place of destination is either directly or indirectly connected to the ground, or directly or indirectly supported in or on the ground, intended to function locally."

And to further complicate matters, according to the Ministry's mandated definition document (the SVBP 2012), the zoning world defines a structure as follows:

"A building structure of any size that is directly and durably connected to the earth."

And what is that "directly and durably connected to the earth"?

The court finds that a piece of string used to tie up the boat is sufficient, as long as the thing is intended to function on site. And although, curiously, we thus have no unambiguous definition of the term structure, the highest court has now spoken. A houseboat is a structure and must therefore, among other things, comply with the building code. And that's not so easy.

What goes wrong?

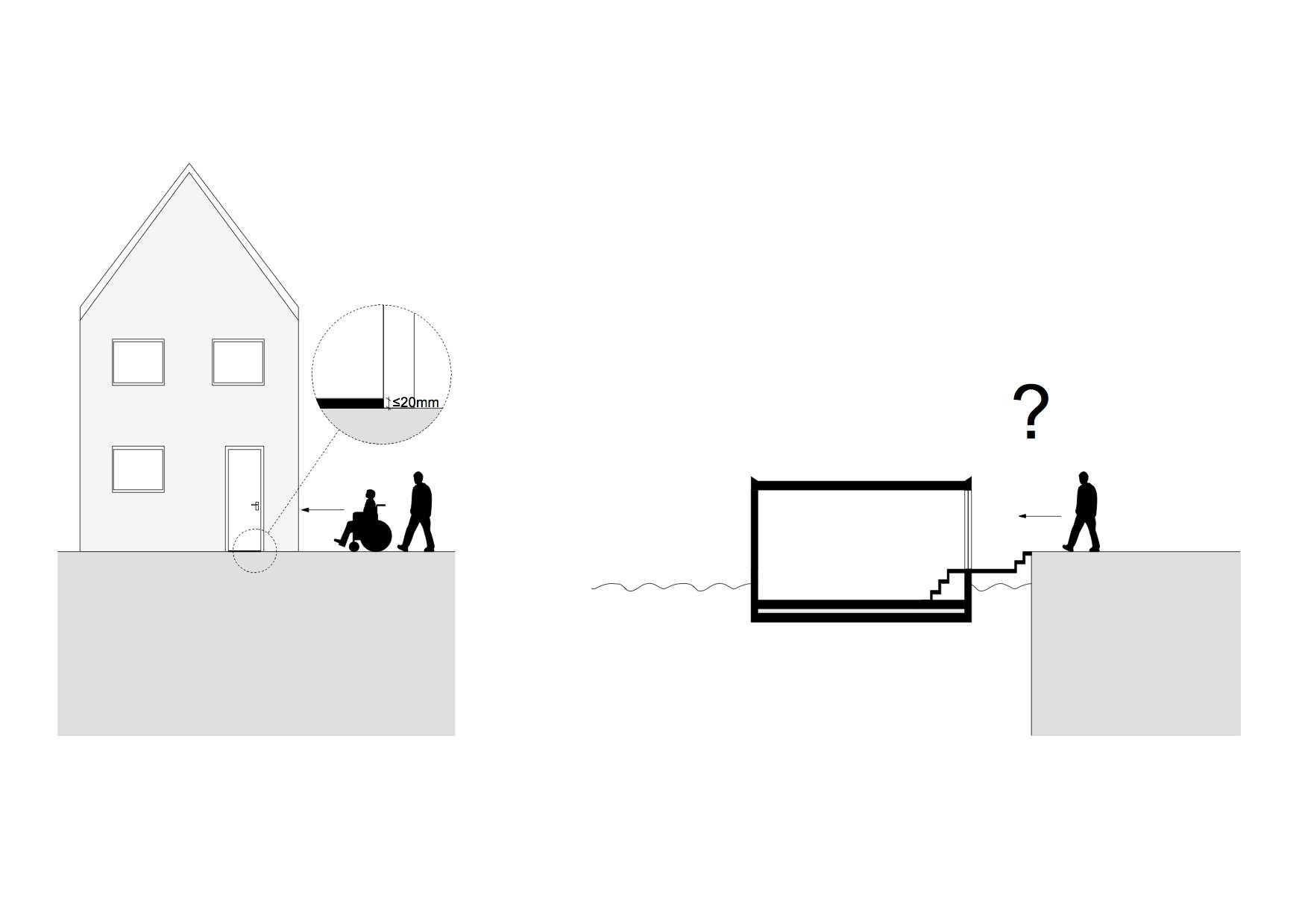

- To start with the front door, the height difference from the connection to the adjoining ground floor must not exceed 20 mm, according to the building code. Just try to get that done from a quay wall that is one-and-a-half metres above the water line and a ground floor of a houseboat that is one-and-a-half metres below the water line.

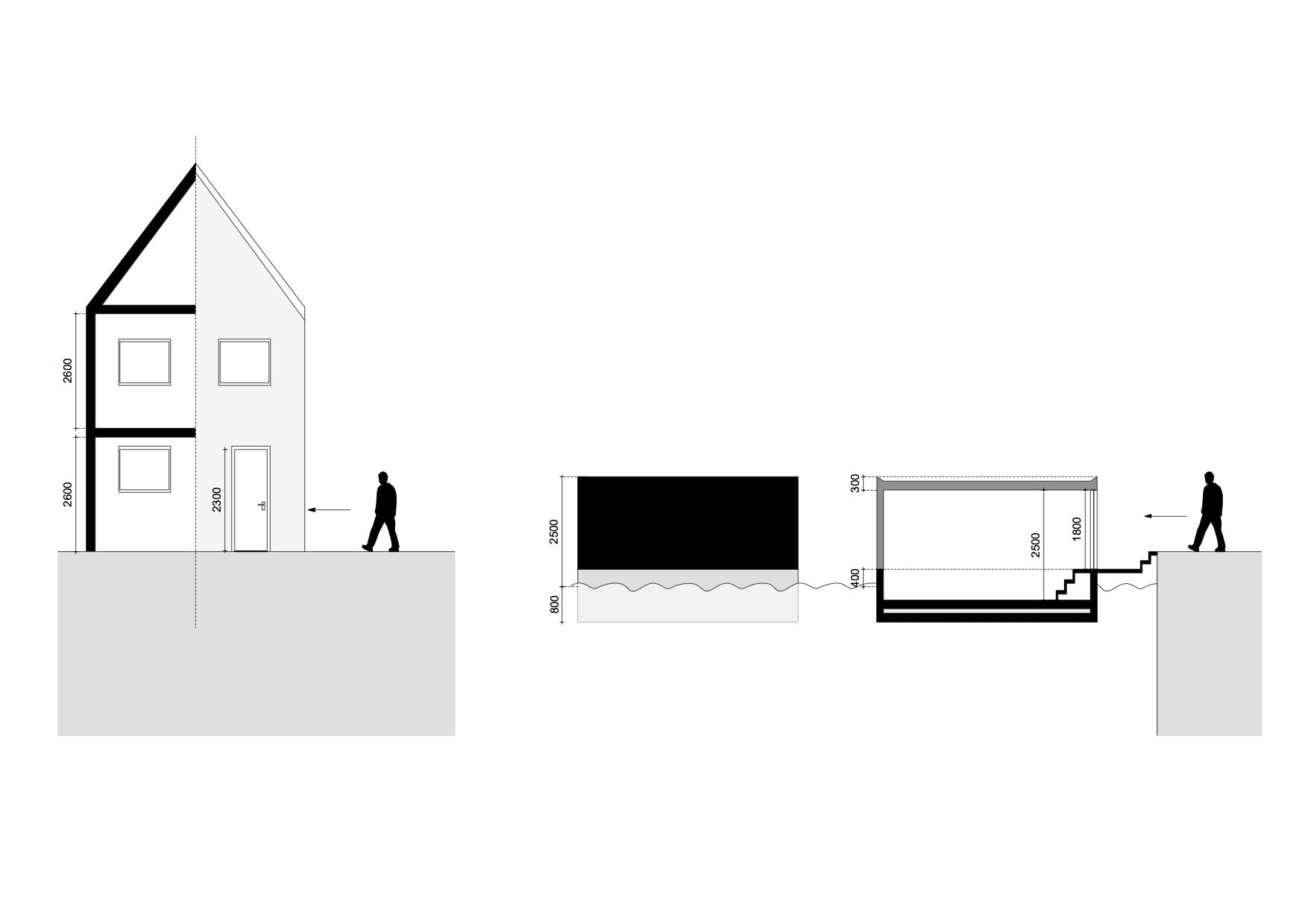

- Or what about provisions on clear height and free passage height. The building code prescribes a free height of 2.6 metres and a free passage height of 2.3 metres. The maximum height of a houseboat is generally set by municipalities at 2.0 to 3.0 metres above the waterline. This is understandable, in order to maintain some view of the water from the shore. With a freeboard (the height above the waterline of the watertight construction part) of 0.3 to 0.4 metres, necessary in connection with flooding, wave action and insurance, a maximum building height of 2.5 metres leaves you with only 2.1 metres to make a door. And that still needs a frame, sill and roof. So then it doesn't work.

The same problem occurs with the normal clear height (2.6m) that an accommodation space must meet. Again assuming a maximum height above the waterline of 2.5 m, from which a roof edge of 100 mm, a roof insulation of 100 mm and a roof construction with a slope, together easily 300 mm must be subtracted. Then you quickly lose the first 0.5 metres. If we add to that the required clear height of 2.60 metres, the top of the ground floor is 0.6 metres underwater. If we then add a normal insulated VBI concrete floor with a sand-cement screed of about 350 mm and a "crawl space" for ventilation, hull inspection and pipework of 0.5 metre and, of course, the floor of the concrete container itself of 150 mm thick, then all in all we are at 1.60 metres underwater. And it's not that deep along the waterfront in the Netherlands. Another disadvantage is that the parapet of the windows will then be 1 metre high. Looking out from your armchair is then out of the question.

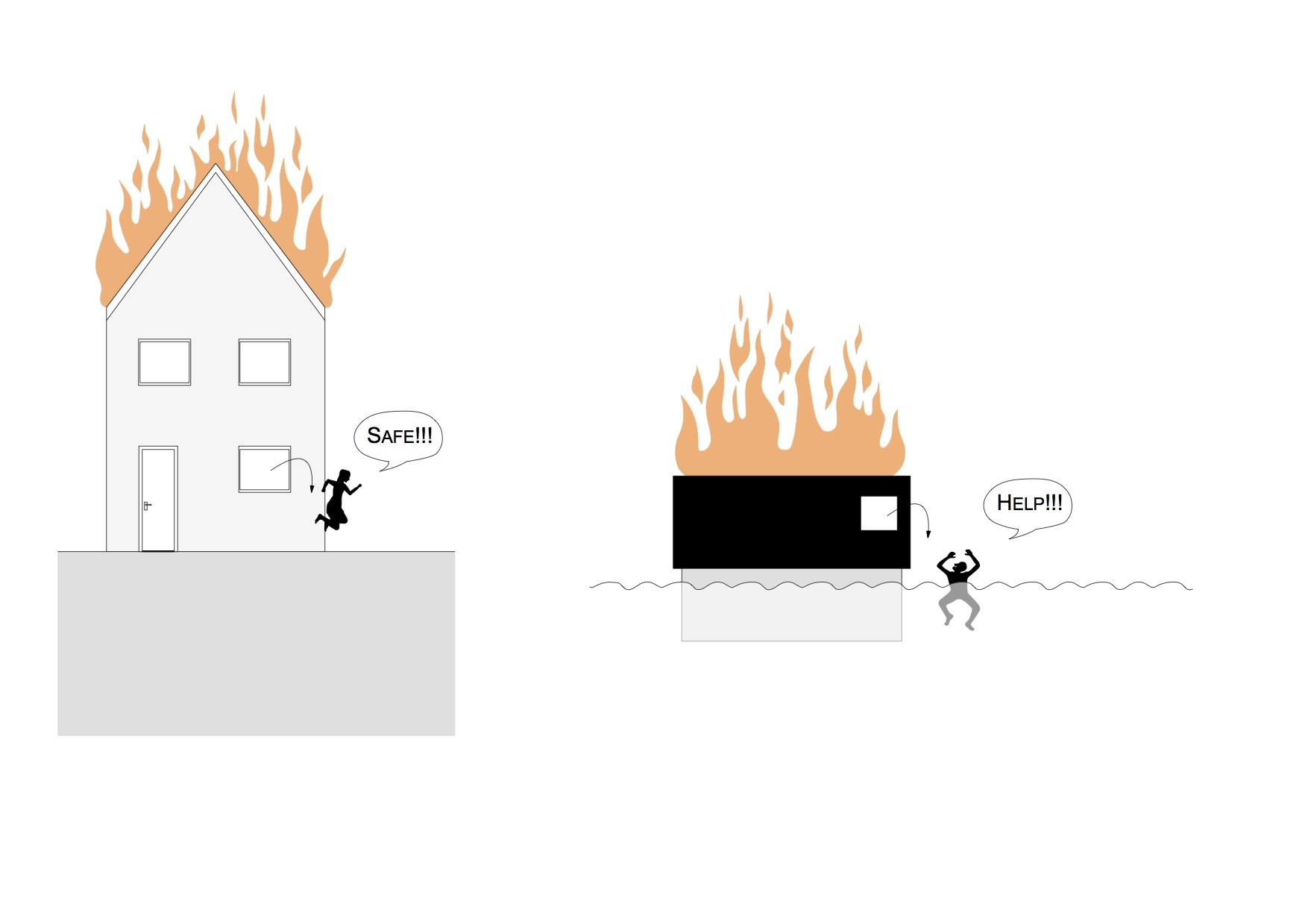

- In the Building Regulations, escape, for example for fire, takes place to the so-called adjacent terrain. Now, the contiguous terrain of boats is generally water or a jetty/quay/shore. And while a nice pike dive out the window into the water in case of a fire on a boat might seem like a better escape route than jumping out the window of a house into the front yard, it is not considered equivalent by regulators.

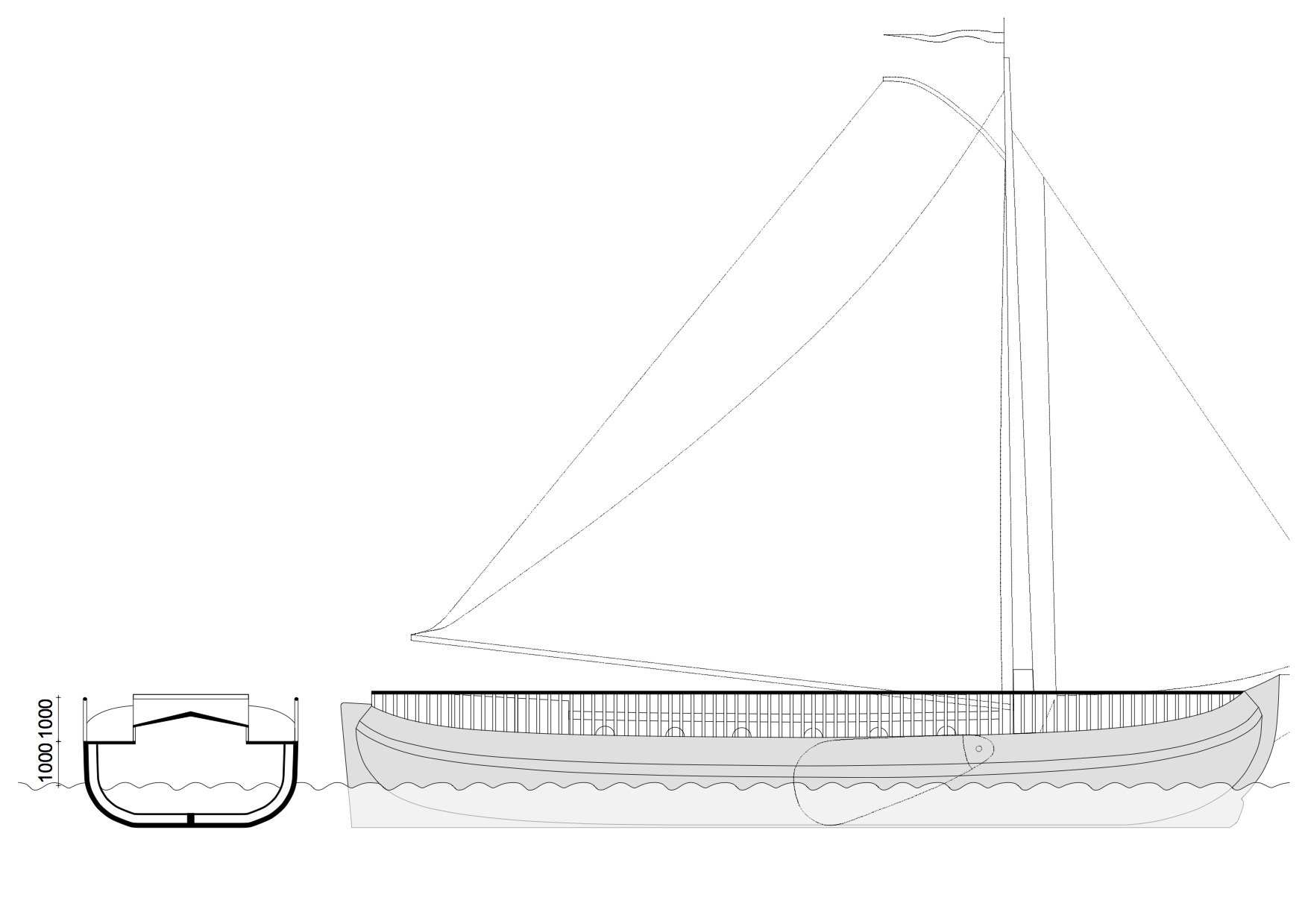

- Or what about a non-overclimbable fall-through protection of the right height on a Tjalk, to avoid falling into the water from a metre high. In any case, it is impossible to make an original ship, sometimes just 100 years old, comply with the building code. There is probably no one who really wants to either, and banging your head mercilessly is unfortunately a bit part of the deal on those things. And what are you supposed to do when you live in a beautiful as good as original Klipper or Tjalk? You could sail away with it like that, but the highest court has now ruled that you have a structure and no longer a ship. Just because your vessel is properly tied up and connected to utilities and functioning on site.

- Or what about a non-overclimbable fall-through protection of the right height on a Tjalk, to avoid falling into the water from a metre high. In any case, it is impossible to make an original ship, sometimes just 100 years old, comply with the building code. There is probably no one who really wants to either, and banging your head mercilessly is unfortunately a bit part of the deal on those things. And what are you supposed to do when you live in a beautiful as good as original Klipper or Tjalk? You could sail away with it like that, but the highest court has now ruled that you have a structure and no longer a ship. Just because your vessel is properly tied up and connected to utilities and functioning on site.

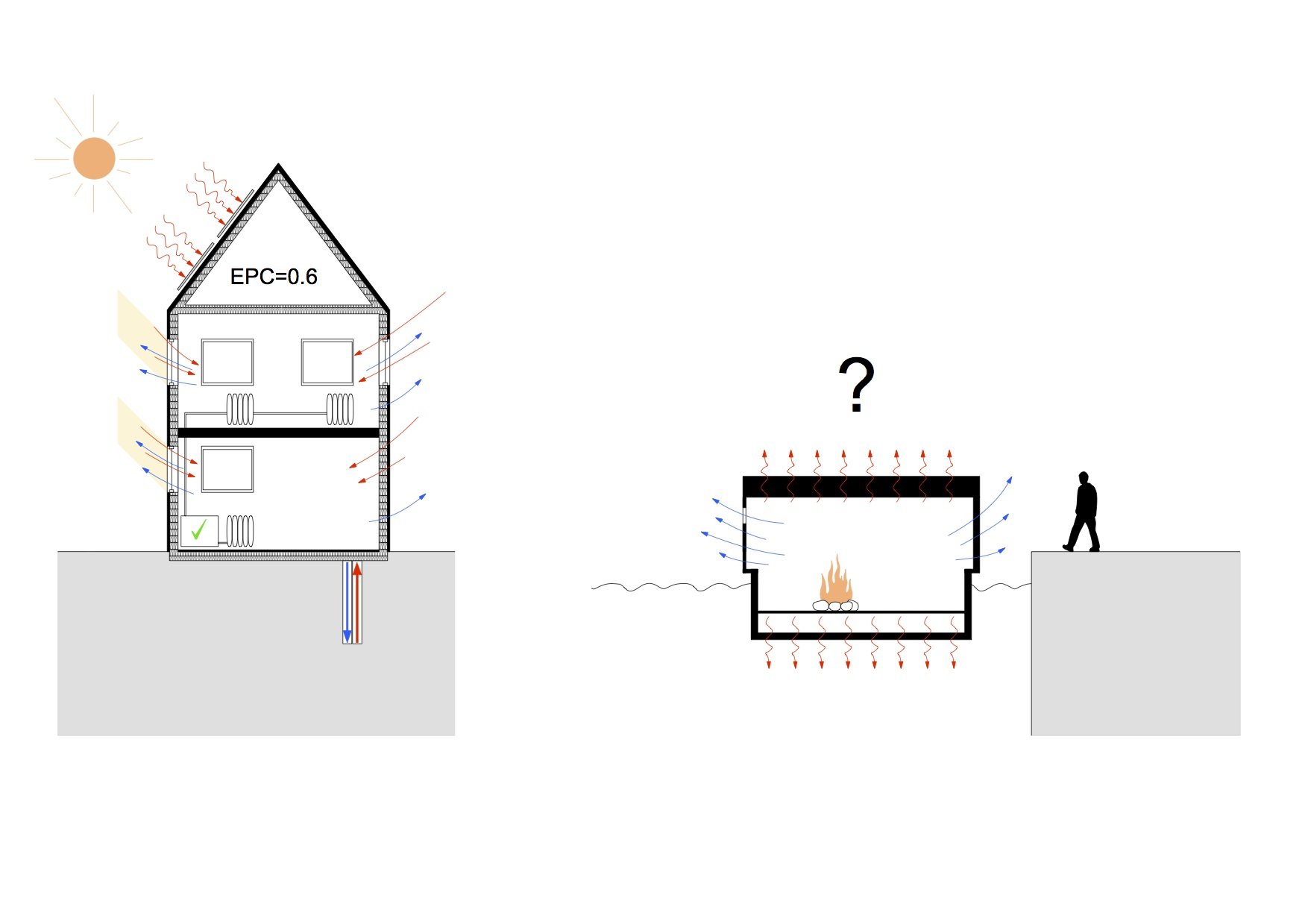

All this, by the way, is not a plea for no regulation on water. Indeed, there are issues where the lack of regulation of houseboats compared to houses on shore creates glaring legal inequities. For example, an EPC trending from 0.6 now and 0.4 in 2015 slowly towards 0.0 for houses on shore is now fully accepted, but you are still allowed to build a new houseboat without any insulation or double glazing whatsoever, where to get warm you merrily burn painted wood, diesel or, even cheaper, lettuce oil from the Aldi all winter long. As a result, entire canals and harbours are sometimes shrouded in thick 19th-century smoke for winter months. We can be romantic about that but actually it is strange that we accept that in the 21st century.

Whereas an owner of an Amsterdam canal house located in a Unesco World Heritage site is no longer allowed to make any substantial changes to his building, the owner of a houseboat floating three metres down the canal is allowed to do just about anything.

In short, something needs to be done, and fast. For caravans we have had a kind of parallel building code for ages. Every article or table has a separate section for caravans. But whether it is such a good idea to start developing yet another "parallel" building code for houseboats, ships and floating houses is the question.

It is undoubtedly the quickest and cheapest way to make some emergency legislation and solve the worst gaps and problems. But wouldn't it be much more interesting to use the legislation that has to come in place for houseboats anyway to test what the much-desired flexible regulations might look like? How can we create a regulation that allows maximum freedom but guarantees safety, usability and beauty? A regulation that does not prescribe and punish, but rewards and encourages. Especially in zoning plans. And then preferably go all the way and integrate the zoning plan with the building regulations into a single document. A regulation where maximum freedom goes hand in hand with maximum spatial quality. Such an experiment might be more interesting than making the existing land regulations as waterproof as possible.

This article was also published on Archined.nl and is based on an extensive study of regulations on water and spatial quality that was made possible thanks to a contribution from the Stimuleringsfonds voor Architectuur, now Stimuleringsfonds voor de Creatieve Industrie. All the drawings are part of the report of that research.

Jasper de Haan is an architect and advisor on houseboats to the Amsterdam Commission for Welfare and Monuments, he is writing this article in a personal capacity.

For the full research report "Landlubbers on the water" click here (1.79 MB)